Continuous delivery at work

29 Oct 2017This is a sort of writeup of my talk given at DevOps Days Edinburgh this week. I’ve reordered some of what I said in the talk since this is a blog post. Slides are here

For around about 6 or 7 months now deployment pipelines have been a hot topic of conversation at work in the context of Kubernetes. I really enjoy this sort of work because it’s an area where you can make a big change in the way developers integrate their workflows with the underlying infrastructure in a good way. When users complain about something or say “it’d be good to have x” my team gets to be the people who shape that idea and can have some well reasoned and interesting discussions about how to improve their situation.

This is particularly pertinent given I’ve used our other deployment processes at work, and they were aweful, for the following reasons

Getting a big picture was hard

The problems

If it’s hard or time consuming to know

- What’s in prod

- Who owns said things in prod

- What version said things are at (whether that be a semver or commit hash)

…it becomes difficult to feel confident when things go badly.

What’s in prod?

Firstly, it’s hard to track and understand the resource requirements of your system without knowing what’s there in the first place.

Who owns said things in prod?

Secondly, if you can’t talk to the owner of x or y microservice, informing that person that I don’t know, they’re causing problems with the underlying infra by using it incorrectly or they’re using up to much space can be tricky.

What version is said thing on?

Finally, if someone rolls out a new version of x, but you don’t know what version it was on previously, and that microservice deployment fails or else causes interraction problems, tracking down what changes happened and whehter they’re related to the problem becomes kind of guess work depending how far from the problem you are as a support engineer.

In my previous job I spent several hours literally going through the svn logs and jumping to that change, trying it out and marking it broken or not. Git probably has better tools for handling that, but the amount of changes you have to go through if you know the two version numbers/tags etc is much smaller.

What we did about this

The main “concept” or tool we’re using to avoid this is GitOps. Essentially, it means your infrastructure, whether that’s a k8s cluster, a cloudformation deployment, whatever, is represented as a git repo. CI/CD pipelines are used to deploy everything, so an addition/update/rollback is represented as a merge request. Weaveworks write quite a lot on this topic

Version 0.1

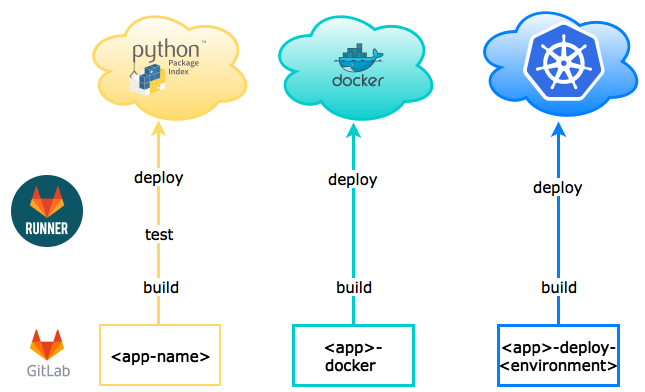

Initally we had something like this:

- Microservices in whatever language are built/tested/deployed through CI to their appropriate package manager from their repo (TMI: we have Nexus instances as the central source for those package managers)

- A second repo builds the docker image and deploys it to our private container registry (again, Nexus based)

- A third repo deploys it (and only it) to an appropriate environment

Why is this only version 0.1?

Mainly, the problem here is we have a lot of microservices, and a lot of environments. If every microservice demands it’s own repo to deploy it, we haven’t really improved the first problem (knowing what’s in prod) because we need to go through all of the repos for that environment. As a consequence, the same goes for the third point (knowing what versions are in prod).

This layout is also going to lead to a lot of duplication - most of what’s in the Kubernetes yaml files for each app won’t change from one environment to another, but yet we have it duplicated in every repo.

It’s also not particularly secure or maintainable. Lots of different repos have full access to change the state of the cluster, and lots of engineers will need to add and remove stuff from those repositories so will probably have access to your deploy keys etc by virtue of having that right. From a maintainability perspective if I need to deploy an updated version of the pipeline scripts, I have to go through all of those repos updating the version tag for those scripts.

Version 1.0

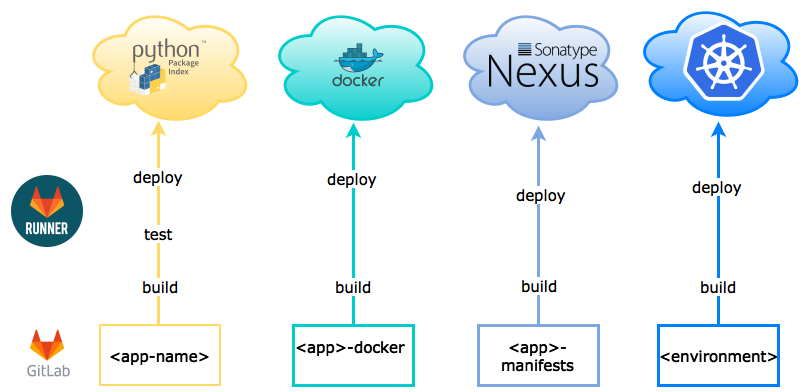

As above, but:

As above, but:

- We add a repo which builds the yaml manifests and bundles them into a tar, which is put in a raw Nexus repository

- The deployment repo deploys not only the application, but all applications. This is done through some raw yaml files, but mostly, urls to those tar files we deployed in the previous repo.

What’s better about this?

We’re not duplicating everywhere, and we have one repo per environment, so you know by looking at that repo what’s on the cluster, rather than going through all the env repos.

What’s bad about this?

In order to update an app, (assuming it requires a code change) you have to submit, at minimum, 4 merge requests. Add one for every environment you want to deploy the new version into and this becomes a pain to manage.

To get around this we wrote a bot which runs once an hour, talks to Gitlab and gets a list of projects to submit suggestions to, then talks to Nexus/Private container registries and checks whether referenced projects have been updated. It then submits a MR with a full changelog generated from that repo.

We had some other stuff to deal with, like we added validation of Kubernetes yaml against a “minimal” K8s apiserver (i.e an etcd container and a bootkube container running pointed at that container) to the pipeline to make sure half completed deployments didn’t happen, deleting stuff required some thought (we went with applying labels to everything with a timestamp as the value, then deleting anything that had the label set to anything else), and I had a fun week of doing Test Driven Bash Development so that we could avoid testing pipeline changes on clusters people were using.

Incomplete or non-existent documentation

The problem

If the whole process isn’t documented clearly, we could end up in several, bad scenarios:

-

You could add a feature to the pipeline which users don’t know exists. They’re not going to ask you about it because they don’t know they can ask about it, so you just spent a whole load of time writing a potentially time saving feature of automation and nobody uses it.

-

A user could misuse the pipeline and end up destroying something. That probably indicates your pipeline is crap and there’s problems underneath your docs problem, but if you at least write down all of the pitfalls and highlight them to your users, then they don’t end up dealing with incidents which could have been dodged.

-

Users could end up spending weeks or months trying to deploy, not to mention the time they might spend talking to other engineers about the problem which causes multiple people to context switch.

What we did about it

Basically, write down all of the things, but specifically:

-

Make your docs be in one place. We had issues where our docs were spread over gitlab, wiki, Google sites, Google docs due to organisational change, so this time around we made sure everything is in Gitlab and users of our pipelines are made aware where that is.

-

Peer review them. Specifically what works well for us is making the full team aware of it and hopefully, waiting for feedback from someone experienced in that area (i.e the k8s concept you’re addressing, not what we’re doing with it) and someone who knows little to none about that area (maybe someone who’s actually using and deploying via your pipelines). That’s probably just good advice for anything you do, but in this case it helps us to pick up bits that seem clear but really aren’t.

-

Make them concise but with lots of examples. I hate reading really really over wordy docs, I want to know how to get running and to do it fast. However with k8s it’s a good idea to give a lot of examples of yaml you’re using and that you explain that yaml.

-

Keep them up to date. Generally write down stuff at the time you had the problem or added the feature, but later on try to keep on top of any holes and remind people when they’ve forgotten to document the area.

-

Avoid duplicating upstream and follow best practice. Particularly we have a few guides for doing different things. We write these on our local docs usually because there’s something about the way we’re doing k8s which is different to other people or there’s some quirk of the pipeline we need to make a note of, but we reference upstream a lot.

Thing with k8s is the docs are so extensive that it can be hard to navigate them sometimes unless you know what you’re looking for, so there probably is a doc for what you need you just need to know how to sew it together, so providing links to relevant details is a good idea.

In addition to these “guidelines” we also do template repositories, with the intention being they show how we suggest you use the pipeline. Users then fork them or copy out all the files into their own repo, and we give clear instructions on what to do with the output etc. This helps to communicate when we change or add to the pipeline, but also allows us to easily set up new clusters since we do templates for stuff we have to manage too.

One size doesn’t fit all

Developers don’t work well when you put all of them in the same box. Any processes we create or manage should aim to be consistent, but not limiting in what developers can and can’t do.

For example, previous processes used templating languages and internally developed tools, and both of those were requirements of the pipelines which helped people maintaining the infrastructure to work faster, but slowed down and caused irritation for development teams.

What we did about it

Avoid rules, unless you really, really need them. This involves talking to current users but taking what they need with a pinch of salt or a stepped back view on the process as a whole.

Any time feature requests or pain points come up, ask yourself - is there another way they could do this? How is this going to harm or hinder other people’s needs and workflows?

Did that work?!

Finally, any deployment process should be able to tell you whether the deployment went ok without you putting in too much effort. Previously our developers had to ssh in to each instance of their deployment and run commands to work out whether the container started ok, which isn’t scalable and is just generally fairly boring.

What we did about it

Mostly, this is solved through the tooling choice, i.e Kubernetes means your instances are all visible and checked through one interface. In addition to this though we provide slack integrations telling users when new deployments occur/whether they succeeded, we have monitoring for the platform itself and we have different access levels depending on what your needs are as a developer.

Eventually we’ll be able to provide role based access control (RBAC) by user, but right now we have:

- readonly access when you’re just checking that something went ok

- developer access for when you need to poke about a little bit

- admin access when something goes horribly wrong and your time is limited so you need to just fix it then (presumably) go back to the git pipeline and fix it permanently.

Obviously, having full admin access kind of negates the first two access levels, so we have that disabled by default and provide explicit instructions for how to enable it on a per-namespace basis, with a heavy emphasis that

- This is temporary and you should disable it when you’re done fiddling

- That we don’t have fine grained access control, so when you provide your dev team with admin access to your namespace, you provide admin access to all dev teams.

Giving instructions for admin access and enabling it via merge request enables our team to avoid being the police and cut out a step in the support chain (i.e devs don’t have to go back and forth from us to do what they need to do), but also ensures it’s easy for us or other more relevant admins to review whether it’s necessary and roll it back when the problem is resolved.

Summary

All of what we’ve done comes down to making the pit of success as wide as possible for all users. I don’t know whether it’s perfect but it’s a good jumping off point, and if users need to alter it or ask us to improve it we’re very open to suggestions.